A study finds that the herb milk thistle may help treat liver inflammation in cancer patients who receive chemotherapy. Published early online in Cancer, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, the study indicates that the herb could allow patients to take potent doses of chemotherapy without damaging their liver.

Chemotherapy drugs frequently cause inflammation in the liver, and when they do, doctors must often lower patients’ doses or stop administering the therapies altogether. Clinical studies have investigated using milk thistle to treat liver damage from cirrhosis (from alcohol) or toxins (such as mushroom poisoning). Despite limited study data, the herb is often used for the treatment of chemotherapy associated liver problems. To test whether milk thistle could help treat chemotherapy associated liver problems, Kara Kelly, MD, of the New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center’s Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York City and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled, double blind study in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), who commonly experience this side effect.

Fifty children with ALL were enrolled in the study and were randomized to receive milk thistle or placebo for 28 days. At the start of the study, all of the children had evidence of liver inflammation as measured by elevations in blood levels of the liver enzymes, aspartate amino transferase (AST) and amino alanine transferase (ALT). When the investigators performed liver function tests on the children at day 56 (28 days after receiving the herb or placebo), children receiving milk thistle had improvements in their liver enzymes compared with children receiving a placebo. Specifically, the group that took milk thistle had significantly lower levels of AST and a trend towards significantly lower levels of ALT. Taking milk thistle also seemed to help keep fewer patients from having to lower the dose of their medications: chemotherapy doses were reduced in 61 percent of the group receiving milk thistle, compared with 72 percent of the placebo group. In addition, milk thistle appeared to be safe for consumption.

The researchers also studied the effects of combining milk thistle with chemotherapy on leukemia cells grown in the laboratory. They found that milk thistle does not interfere with the cancer-fighting properties of chemotherapy.

“Milk thistle needs to be studied further, to see how effective it is for a longer course of treatment, and whether it works well in reducing liver inflammation in other types of cancers and with other types of chemotherapy,” said Dr. Kelly. “However, our results are promising as there are no substitute medications for treating liver toxicity.”

The Cinnamon Conspiracy: Why Your Everyday Spice Might Be Toxic – and the Superior Alternative You Need to Know

The Cinnamon Conspiracy: Why Your Everyday Spice Might Be Toxic – and the Superior Alternative You Need to Know Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report

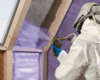

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit?

Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit? Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’

Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’