Exposure to X-rays and gamma rays, even at low-dose levels, increases risk of cancer. That is the bottom line of a comprehensive five-year study by a National Research Council (NRC) committee that included Stanford’s Herbert L. Abrams, a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences.

Exposure to X-rays and gamma rays, even at low-dose levels, increases risk of cancer. That is the bottom line of a comprehensive five-year study by a National Research Council (NRC) committee that included Stanford’s Herbert L. Abrams, a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences.

“There appears to be no threshold below which exposure can be viewed as harmless,” said Abrams, professor emeritus of radiology at Stanford and Harvard universities and a member in residence at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) in the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Abrams was one of two physicians and the only member from Stanford on the committee of 16 international experts in fields including epidemiology, radiation biology, genetics, cancer biology, radiology and physics. As a radiologist, Abrams said he “was able to serve as a bridge between the epidemiologists and the biologists on the committee, whose approaches to risk were based on completely different data sets.”

The landmark 700-page advisory report to the U.S. government, titled “Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR) VII,” was completed in July, near the eve of the 60-year anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. It is the seventh report in a series since the 1945 atomic bombings to investigate the effects of low-level radiation exposure. The reports provide U.S. policymakers and health agencies with authoritative risk estimates. Beginning with the first BEIR study, published in 1956, the reports have used data from the Life Span Study by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation in Japan, which continues to track developments among a cohort of 120,000 people who were in Hiroshima or Nagasaki at the time of the bombings, as well as other radiation-exposure studies.

The NRC convenes BEIR committees periodically, at the request of U.S. government agencies, to decide whether sufficient new information is available to merit an updated study, and if so, to conduct it. This process has yielded BEIR reports I, III-V and VII, which assess low-level radiation risks in general, and BEIR II and VI, which focus on radon gas effects.

BEIR VII, sponsored by the U.S. departments of Defense, Energy and Homeland Security and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, “provides the most up-to-date, comprehensive estimates for risk for cancer and other harmful health effects from low-dose radiation,” according to the NRC. The committee reviewed not only new data on A-bomb survivors and their offspring but also 1,300 other studies on radiation exposure at the cell, animal and human levels, Abrams said. Since the 1990 publication of BEIR V, “substantial epidemiologic and experimental research has yielded a wealth of new information on radiation-induced cancer, as well as other adverse health impacts,” he added.

The new report confirms that even very low doses of radiation can produce cellular injury. The committee defined “low-dose” as a range from near zero up to about 100 milliSieverts—about 10 times that from a CT scan, 1,000 times greater than a mammogram and 30 to 40 times the annual background exposure a person encounters. Background radiation from the natural environment—including outer space, the ground, and basic activities such as eating, drinking and breathing—accounts for about 82 percent of human exposure, while man-made radiation from sources including medical X-rays and consumer products accounts for the remaining 18 percent. Progressive exposure to such radiation causes DNA damage, Abrams said, which correlates with an increased risk of developing a variety of cancers. While the report examined a range of potential health risks, it focused on causal relationships to solid cancers in humans.

The report is among the first of its kind to include detailed estimates for radiation-induced cancer incidence and mortality, Abrams said. The report enhances prior risk estimates for solid cancer and leukemia, using risk models based on a gender and age distribution similar to that of the entire U.S. population. The committee estimated the excess lifetime risks for 12 categories of cancer.

Major findings

For boys, radiation exposure in the first year of life produces three to four times the lifetime cancer risk as exposure to the same dose between the ages of 20 and 50. Female infants have almost double the risk as male infants.

For women, the risks of developing cancer after exposure to radiation were 37.5 percent higher than for men. The risks for all solid tumors, such as lung and breast tumors, when added together, were almost 50 percent greater for women than for men. But for a few specific cancers, such as leukemia, the radiation-induced risk estimates were higher for men.

Examining data on children of A-bomb survivors, the committee did not find genetic effects in children whose parents had been exposed to radiation from the bombs, but exposure of the fetus during pregnancy was associated with significant damage to the brain, including mental retardation. Studies of mice and other organisms have produced extensive data showing that radiation-induced cell mutation in sperm and eggs can be passed to offspring, the committee reported. Such mutations might also be passed on to human offspring, but their detection might require a survivor population larger than that of the children of A-bomb survivors.

What’s next?

The report identified key areas for further research:

# Determining various molecular markers of radiation-caused DNA damage. # Examining adverse genetic impacts, with particular emphasis on the hereditary effects. # Elucidating the specific role of radiation in the development and growth of tumors. # Clarifying the genetic factors that influence radiation response and cancer risk, as well as the correlation between radiation and other diseases such as heart disease and stroke. # Exploring the health effects of radiation exposure to patients in the practice of diagnostic radiology—such as repeated screening CT scans—and in high-risk occupations such as nuclear industry workers and uranium miners. # Conducting epidemiologic studies of workers in these high-risk jobs as well as persons exposed in key regions of the former Soviet Union and remaining atomic bomb survivors.

Studies in these areas could inform the next BEIR report, when enough new data accumulate to warrant an update.

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report

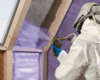

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit?

Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit? Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’

Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’ A daily dose of yogurt could be the go-to food to manage high blood pressure

A daily dose of yogurt could be the go-to food to manage high blood pressure