A diet high in sugar and fat such as burgers, fries and fizzy drinks can negatively affect a new mother’s breast milk and baby’s health even before the child is conceived.

The new study using lab mice has found that even relatively short-term consumption of a fast food diet impacts women’s health, reducing their ability to produce nutritional breast milk after giving birth. This can affect the newborn’s wellbeing, as well as increasing the risk of both mother and child developing potentially fatal conditions such as heart disease, stroke and diabetes in later life.

Even mothers who appear to be a healthy weight can be suffering from hidden issues such as a fatty liver — which may be seen in people who are overweight or obese — from eating a diet heavy in processed foods, which tend to be high in fat and sugar. This can lead to advanced scarring (cirrhosis) and liver failure.

The new findings involved scientists from the Sferruzzi-Perri Lab at the Centre for Trophoblast Research, University of Cambridge, and The Department for the Woman and Newborn Health Promotion at the University of Chile in Santiago, and are published by the journal Acta Physiologica.

Co-lead author Professor Amanda Sferruzzi-Perri, Professor in Fetal and Placental Physiology and a Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge, said: “Women eating diets that tend to have high sugar and high fat content may not realise what impact that might be having on their health, especially if there’s not an obvious change in their body weight.

“They might have greater adiposity — higher levels of fat mass — which we know is a predictor of many health problems. That may not overtly impact on their ability to become pregnant, but could have consequences for the growth of the baby before birth, and the health and wellbeing of the baby after birth.”

It is already recognised that a ‘Western style’ diet high in fat and sugar is contributing to a pandemic of raised body mass index (BMI) and obesity not only in developed countries but also in developing nations undergoing urbanisation, including Chile. As a result, just over half of women (52.7%) in many populations around the world are overweight or obese when they conceive, leading to problems in both achieving and maintaining a healthy pregnancy.

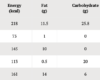

Obesity has been recreated in mice before, but most studies focus on the effects of chronic, long-term high fat, high sugar diets. In this new study, a group of mice was fed a diet of processed high fat pellet with sweetened condensed milk for just three weeks before pregnancy, during the three-week pregnancy itself, and following birth. This diet was designed to mimic the nutritional content of a fast food burger, fries and sugary soft drink. The aim was to determine the impacts on fertility, fetus growth and neonatal outcomes.

The researchers discovered that even a short-term high fat, high sugar diet impacted on the survival of the mice pups in the early period after birth, with an increased loss during the time the mother was feeding her offspring. Milk proteins are hugely important for newborn development but the quality was found to be poor in mouse mothers eating the high fat, high sugar diet.

“We wanted to know what was going on, because the mothers looked okay, they weren’t large in terms of their size. But what we found was that although the mice seemed to have okay rates of getting pregnant, they did have greater amounts of adipose — fat tissue — in their body in and at the start of pregnancy,” said Professor Sferruzzi-Perri.

“They ended up with fatty livers, which is really dangerous for the mum, and there was altered formation of the placenta. The weight of the fetus itself wasn’t affected. They seemed lighter, but it wasn’t significant. But what was also apparent was that the nutrition to the fetus was changed in pregnancy. Then when we looked at how the mum may be supporting the baby after pregnancy, we found that her mammary gland development and her milk protein composition was altered, and that may have been the explanation for the greater health problems of the newborn pups.”

When a woman of larger size is pregnant, clinicians are often most concerned about the risk of diabetes and abnormal baby growth. But in mums-to-be who look healthy, regardless of their food intake, subtle, but potentially dangerous changes in pregnancy may slip under the radar.

“The striking part is that a short exposure to a diet from just before pregnancy that may not be noticeably changing a woman’s body size or body weight may still be having implications for the mother’s health, the unborn child and her ability to support the newborn later,” said Professor Sferruzzi-Perri.

“We’re getting more and more information that a mother’s diet is so important. What you’re eating for many years before or just before pregnancy can have quite an impact on the baby’s development.”

Professor Sferruzzi-Perri said it is important for women to be educated about eating a healthy, balanced diet before trying to get pregnant, as well as during the pregnancy and afterwards. She would also like to see more pregnancy support tailored to individual mothers, even if they look outwardly healthy. “It’s about having a good quality diet for the mum to have good quality milk so the baby can thrive.”

With fast, processed foods often cheaper to buy, Professor Sferruzzi-Perri fears that poverty and inequality may be barriers to adopting a healthy and active lifestyle. She said: “It costs a lot of money to buy healthy food, to buy fresh fruit and vegetables, to buy lean meat. Often, the easiest and the cheapest option is to have the processed foods, which tend to be high in sugar and fat. With the cost of living going up, those families that are already deprived are more likely to be eating foods that are nutritionally low value, because they have less money in their pocket.

“That can have implications not just on their health and wellbeing, but also the health and wellbeing of their child. We also know that this is not only in the immediate period after birth, as unhealthy diets can lead to a lifelong risk of diabetes and heart disease for the child in the longer term. So these diets can really create a continuum of negative health impacts, with implications for subsequent generations.”

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report Blood Sugar Stability the Organic Way: Low-Glycemic Foods and Meal Ideas

Blood Sugar Stability the Organic Way: Low-Glycemic Foods and Meal Ideas Preterm births linked to ‘hormone disruptor’ chemicals may cost United States billions

Preterm births linked to ‘hormone disruptor’ chemicals may cost United States billions Animal vs. Plant Protein: These Protein Sources Are Not Nutritionally Equivalent

Animal vs. Plant Protein: These Protein Sources Are Not Nutritionally Equivalent