This story was originally published by ProPublica.

by Lylla Younes, Ava Kofman, Al Shaw and Lisa Song, with additional reporting by Maya Miller,

Poison in the Air

The EPA allows polluters to turn neighborhoods into “sacrifice zones” where residents breathe carcinogens. ProPublica reveals where these places are in a first-of-its-kind map and data analysis.

From the urban sprawl of Houston to the riverways of Virginia, air pollution from industrial plants is elevating the cancer risk of an estimated quarter of a million Americans to a level the federal government considers unacceptable.

Some of these hot spots of toxic air are infamous. An 85-mile stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana that’s thronged with oil refineries and chemical plants has earned the nickname Cancer Alley. Many other such areas remain unknown, even to residents breathing in the contaminated air.

Until now.

ProPublica undertook an analysis that has never been done before. Using advanced data processing software and a modeling tool developed by the Environmental Protection Agency, we mapped the spread of cancer-causing chemicals from thousands of sources of hazardous air pollution across the country between 2014 and 2018. The result is an unparalleled view of how toxic air blooms around industrial facilities and spreads into nearby neighborhoods.

At the map’s intimate scale, it’s possible to see up close how a massive chemical plant near a high school in Port Neches, Texas, laces the air with benzene, an aromatic gas that can cause leukemia. Or how a manufacturing facility in New Castle, Delaware, for years blanketed a day care playground with ethylene oxide, a highly toxic chemical that can lead to lymphoma and breast cancer. Our analysis found that ethylene oxide is the biggest contributor to excess industrial cancer risk from air pollutants nationwide. Corporations across the United States, but especially in Texas and Louisiana, manufacture the colorless, odorless gas, which lingers in the air for months and is highly mutagenic, meaning it can alter DNA.

In all, ProPublica identified more than a thousand hot spots of cancer-causing air. They are not equally distributed across the country. A quarter of the 20 hot spots with the highest levels of excess risk are in Texas, and almost all of them are in Southern states known for having weaker environmental regulations. Census tracts where the majority of residents are people of color experience about 40% more cancer-causing industrial air pollution on average than tracts where the residents are mostly white. In predominantly Black census tracts, the estimated cancer risk from toxic air pollution is more than double that of majority-white tracts.

The cancer risks from industrial pollution can be compounded by factors like age, diet, genetic predisposition and exposure to radiation; the knock-on effect of inhaling toxic air for decades might, for example, mean the difference between merely having a family history of breast cancer and actually developing the disease yourself.

The locations of the hot spots identified by ProPublica are anything but random. Industrial giants tend to favor areas that confer strategic advantages: On the Gulf Coast, for instance, oil rigs abound, so it’s more convenient to build refineries along the shoreline. Corporations also favor places where land is cheap and regulations are few.

Under federal law, the EPA delegates the majority of its enforcement powers to state and local authorities, which means that the environmental protections afforded to Americans vary widely between states. Texas, which is home to some of the largest hot spots in the nation, has notoriously lax regulations.

The federal government has long had the information it would need to take on these hot spots. The EPA collects emissions data from more than 20,000 industrial facilities across the country and has even developed its own state-of-the-art tool — the Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators model — to estimate the impact of toxic emissions on human health. The model, known as RSEI, was designed to help regulators and lawmakers pinpoint where to target further air-monitoring efforts, data-quality inspections or, if necessary, enforcement actions. Researchers and journalists have used this model for various investigations over the years, including this one.

And yet the agency’s own use of its powerful modeling tool has been limited. There’s been a lack of funding for and a dearth of interest in RSEI’s more ambitious applications, according to several former and current EPA employees. Wayne Davis, the former EPA scientist, managed the RSEI program under the Trump administration. He said that some of his supervisors were hesitant about publishing information that would directly implicate a facility. “They always told us, ‘Don’t make a big deal of it, don’t market it, and hopefully you’ll continue to get funding next year.’ They didn’t want to make anything public that would raise questions about why the EPA hadn’t done anything to regulate that facility.”

Indeed, our map works as a screening tool, not as a site-specific risk assessment. It cannot be used to tie individual cancer cases to emissions from specific industrial facilities, but it can be used to diagnose what the EPA calls “situations of potential concern.”

Our analysis arrives as America faces new threats to its air quality. The downstream effects of climate change, like warmer temperatures and massive wildfires, have created more smoke and smog. The Trump administration diluted, scuttled or reversed dozens of air pollution protections — actions estimated to lead to thousands of additional premature deaths. In 2018, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt created a massive air toxics loophole when he rolled back a key provision of the Clean Air Act, known as “Once In, Always In,” allowing thousands of large polluters to relax their use of pollution-controlling equipment.

Biden has yet to close this loophole, but he has signaled plans to alleviate the disproportionate impacts borne by the people who live in these hot spots. Within his first few days in office, he established two White House councils to address environmental injustice. And in March, Congress confirmed his appointment of EPA administrator Michael Regan, who has directed the agency to strengthen its enforcement of violations “in communities overburdened by pollution.”

The Most Detailed Map of Cancer-Causing Industrial Air Pollution in the U.S.

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report

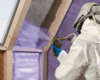

Shocking Glyphosate Levels in Popular Bread: Florida’s Eye-Opening Food Testing Report Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit?

Spray Foam Insulation: Energy Hero or Cancer Culprit? Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’

Compound in Mediterranean diet makes cancer cells ‘mortal’ Air inside your home may be more polluted than outside due to everyday chemical products

Air inside your home may be more polluted than outside due to everyday chemical products